The Legal Aid Society of Northeastern New York (LASNNY) is pleased to announce picturingJUSTICE™. This exhibition will feature photographs that represent what Justice means to the artist, centering around the themes of housing, racial justice, poverty, fair housing, domestic violence, education, food insecurity, LGBTQ+, family, and/or other civil legal issues.

picturingJUSTICE™ seeks to connect our legal work to the people and communities we serve and to open conversations about justice.

Olivia Rose (she/her)

Albany, NY

Floating On Water

In the course of your day you see it. You might see it in your parks, your streets and in parking lots, it’s usually lingering around. But what is it? Pollution. It goes by many names- trash, garbage,litter, but no matter what name you call it, it’s all the same. We all know the effects that pollution has on our world. Climate change, global warming, melting ice caps, etc.

But what’s not discussed enough is the severe impact of pollution on lowincome neighborhoods. When talking about the issue you have to take into account the lack of resources and poor infrastructures. You also have to take in the lack of recreational spaces: such as parks, green areas and sports facilities. Which pollution tends to negatively impact access to safe and clean recreational settings. This single styrofoam cup is a symbol of that. The solution isn’t a simple thing that can be remedied with a day like “earth day” or telling people to ”just pick up after themselves”. To address the impacts of pollution regarding impoverished communities it requires equitable environmental policies, access to clean resources, and community empowerment. This is Floating on Water. Thank you.

Zyaire J. Gaddy (he/him)

Albany, NY

Stil

During the process of taking the photo, it was very quiet. I could hear the wind blowing and I just thought to myself this is the one. I couldn’t help but think about the bench’s past and what it has been through. I even thought about the families that probably once occupied this bench. I felt like the bench was sitting there old and tall watching the neighborhood as certain parts of it change. But the last thought that stuck with me was the truth about this image.

Within this photo holds two different realities. To the right of the photo stands the Empire State plaza. A complex that is worth roughly $2 billion, buildings that required 11 years of labor. The Empire state brings many attractions such as events and tourism. A venue that is appealing to the eye so much so that schools take their prom pictures. But to the left stands a low income housing apartment. What’s interesting to me is that both complexes are hosted in the same neighborhood. On one side you see money and investment, and the other neglect. And yet you have the bench in the center still seeing both sides. This is Stil. Thank you.

Jazlyn Gorousingh (she/her)

Albany, NY

My Melanin Is My Weapon

I wanted to represent Black women differently from how the media represent them. There’s a stereotype that puts Black women in a negative light that I wanted to get rid of. I wanted to show the power we as Black women can have without speaking words. They feel when we speak our passion it comes off as anger or we’re not capable of speaking our mind. This photo gives off so many perspectives of not only women empowerment, but Black empowerment, too. Taking away the stereotypes and making them something beautiful. Showing that no matter what, our features are beautiful. Showing that we’re much more than the box they try to put us in. When Black people come together, we can make something so powerful and beautiful. I want people to embrace that power and melanin when they look at this photo.

Erik McGregor (he/him)

Tappan, NY

Resistance Begin At Home

NYC homeless advocacy coalition members staged a direct action on July 29, 2021 outside City Hall to call out Mayor de Blasio’s Broken Record on Homelessness. Some participants engaged in an act of civil disobedience, resulting in 9 arrests. The group demand that the Mayor and city agencies act immediately to halt inhumane and poorly executed transfers of single New Yorkers experiencing homelessness from COVID-safe hotels into the unsafe congregate shelter system; stop NYPD street “sweeps” of people into the shelter system; and for the Mayor to take immediate action on Intro 146, a bill which require the City to pay higher rates in its rental assistance voucher program for homeless New Yorkers, which are currently so low as to be useless for the majority of people who qualify.

Melissa Breger (she/her)

Albany, NY

At the Crossings of Clinton and Quail

We demand safe housing.

We demand safe streets.

“STOP SHOOTING!” the building cries out to us, as the white chalk starts to fade. An exasperated and frantic flourish of chalk: hopeless, yet hopeful — all at once.

Justice is not just about a place in which we live and a street on which we reside. It is about fair housing, safe streets, clean, affordable housing, safe homes.

Poverty shall never equate to an absence of justice.

We demand justice. For all.

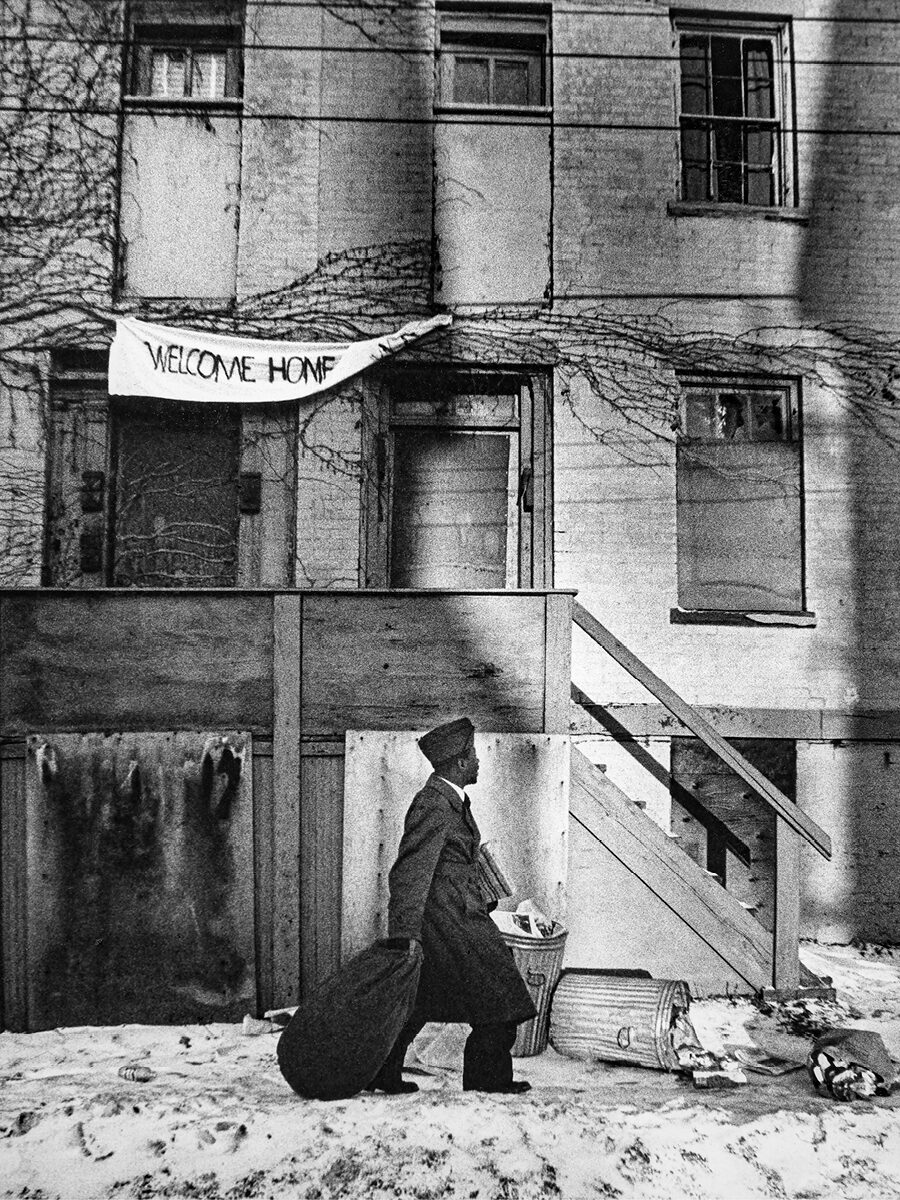

Raphael Warshaw (he/him)

Gainesville, VA

Get Out The Vote

The image selected for this exhibit was taken for New York Magazine in 1971 as part of a “Get-out-the-vote” effort. The model was a custodian at the hospital where I worked. The uniform he wore was mine. I don’t recall how or why the particular building in Poughkeepsie, NY was chosen. We hung the “Welcome Home” sign and the curtains in the upper right-hand window and brought both the trash cans and the trash as props. The members of the neighborhood association arrived shortly after we started shooting to complain that what we were doing was disrespectful. The magazine decided not to use the image because it was “too subtle”. There’s more than a whiff of exploitation to it but the image of a black soldier returning from wartime service to such a neighborhood was and is all too real. Few of he enlisted men I served with bothered to vote believing that it made no difference. Given the gerrymandered districts so many of them came from it was hard to argue otherwise. The soldiers who return from our many wars were and remain, despite being greeted with the infuriating “Thank You for Your Service”, underserved. Much work to be done.

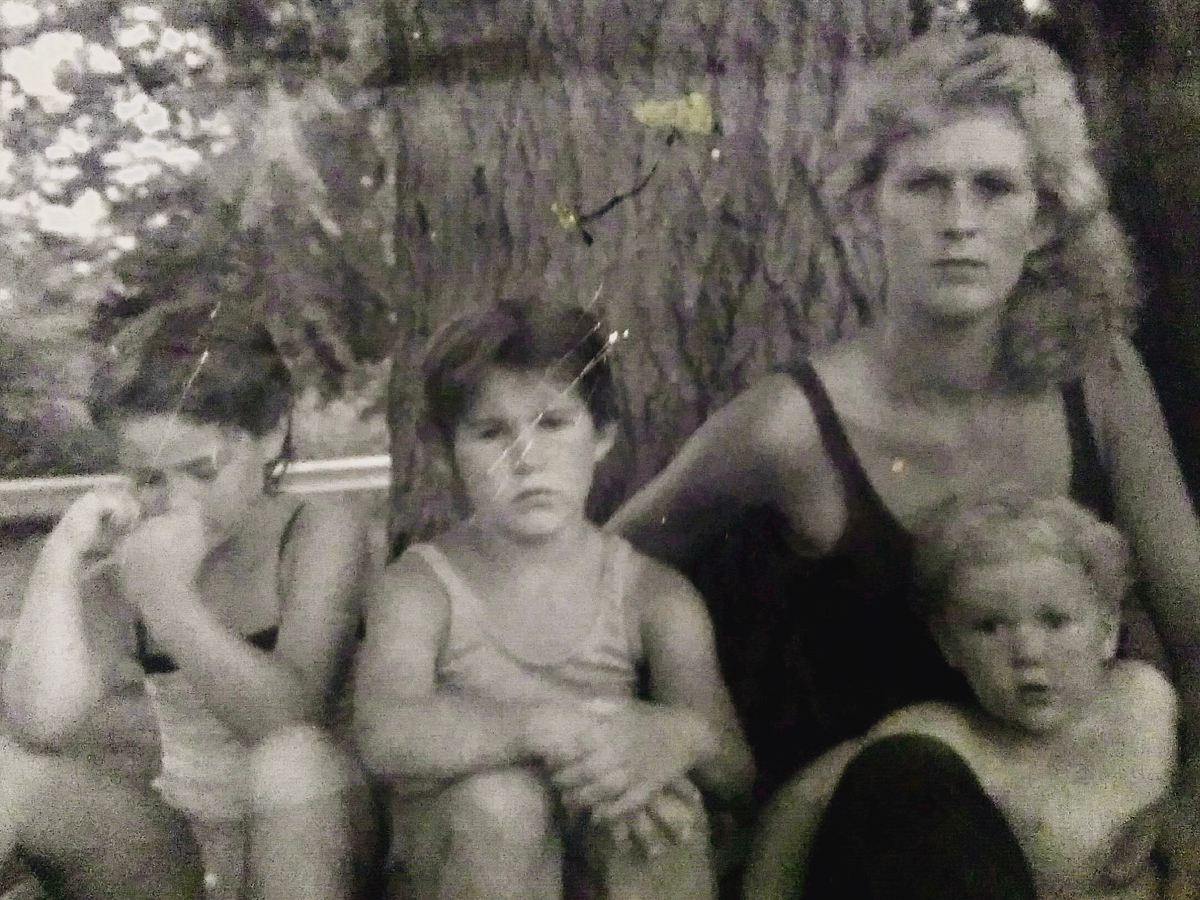

Rebecca Jean

Watervliet, NY

Seeking Refuge

The image of a mother and her three young children escaping the blistering sun under the protection of a large Douglas Fir.

This family has had two fathers abandon their children, the first never to be seen again by his two daughters while he fled to the southwest coast of Alaska. The father of the boy who is sitting comfortably close to his mother will lose his father shortly after this picture was taken the use of drugs and alcohol.

This family found meaning in watching a sunset that lasted only a moment, the admiration of a full and glowing moon.

They told one another about the dreams that came to them only the night before and remained still and silent so they could listen to the sounds of the nearby Church Bell. Although poor, finding a place that would take them away from where they were, would be watching the arrivals and departures of airplanes come and go taking their imaginations with them. Having an experience without actually achieving anything is meaningful.

Scott Langley (he/him)

Ghent, NY

The U.S.’s 1500th Execution

The death penalty is a pressing civil and human rights issue. There is no such thing as a lesser person, and yet, the United States continues to take prisoners out of their cages on death rows across the county to kill them, for what is deemed “justice” by our courts and elected officials. And these selected prisoners are largely people of color, people coming from poverty, and people coming from a general lack of care or security in their communities.

This submitted photo shows a moment outside a U.S. death row during the execution of Marion Wilson, a Black man, in which the prisoner’s young daughter screams “Daddy!” into the night, hugged by an attorney in the case, while other family and friends comfort each other.

This is the horror that the death penalty pepetuates: impossing government sanctioned violence in communities that are already traumatized by social injustice.

To quote from a statement issued by an attorney after this country’s most recent execution: “These people are the collateral damage the death penalty always inflicts. Each premeditated murder by the State creates a new wave of victims. More trauma, more pain – that each of those people will carry home to their loved ones tonight, and carry with them forever.”

While New York does not have the death penalty anymore, the values of LASNNY around equal justice, advancing the rights of the vulnerable and providing legal services on behalf of poor people reflect the power of the attorney-client relationship in transforming injustice in New York’s justice system into a society which is inclusive and equitable for all.

Sydnie Lewis (she/her)

Boston, MA

As I Am.

I believe in the power of art to capture the unique experiences of the LGBTQ+ community and the struggle for justice within it. Through my pieces, I strive to show the beauty, strength, and resilience of truly belonging, and encourage those to express themselves without fear. I hope to capture the struggles, triumphs, and complexity of living in a world where LGBTQ+ individuals’ voices are celebrated by some, while simultaneously still fighting for equality by many. A just world not only allows individuals to express themselves, but recognizes the community’s existence and rights within marriage, relationships, and healthcare.

My work focuses on Justice within the LGBTQ+ community by emphasizing the importance of safe and inclusive healthcare for all – something that often gets overlooked, taken for granted, or misunderstood. I hope to highlight the importance of acknowledging and providing visibility to the needs of the trans community in medical settings, so that all individuals can receive care without fear or stigma. These specific photos represent Justice by bringing attention to the need for accessible and affirming healthcare regardless of gender identity.

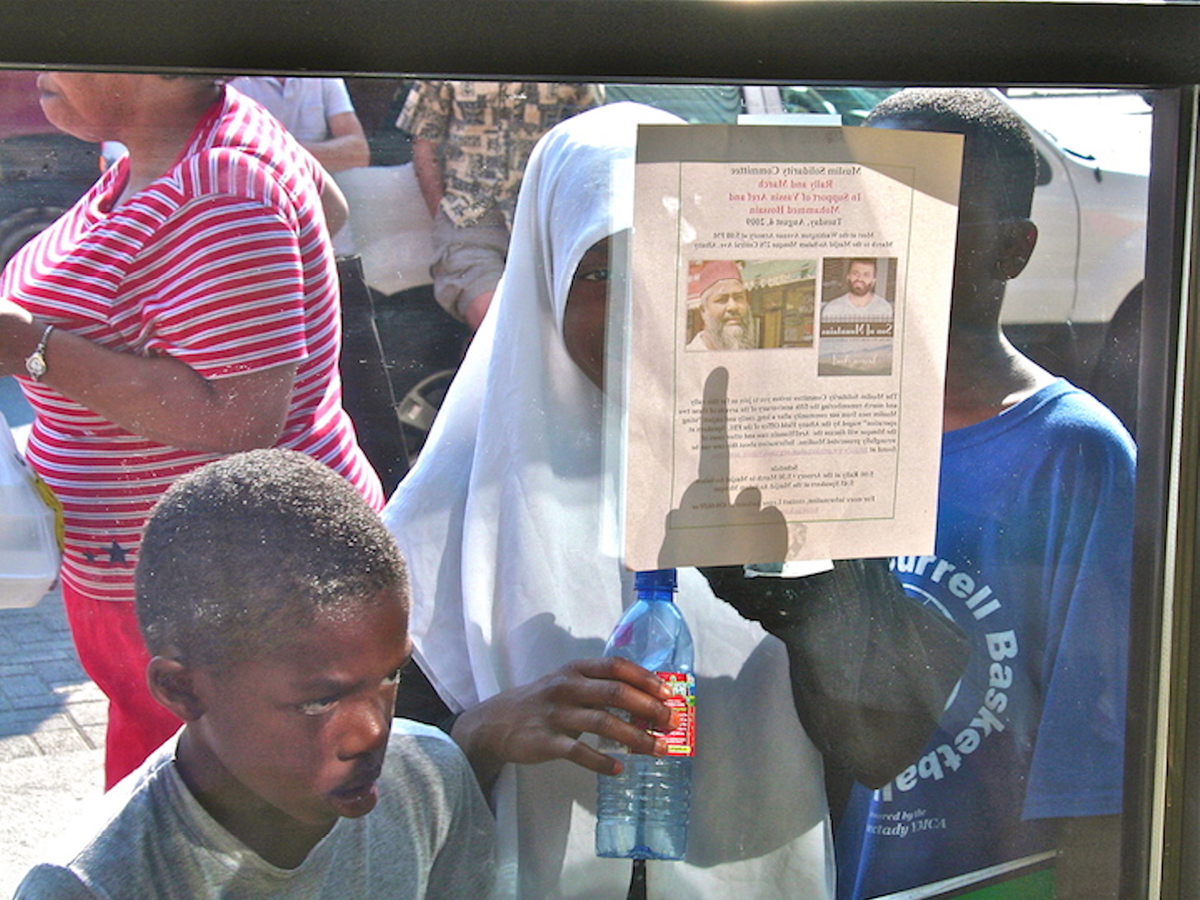

Jeanne Finley (she/hers)

Albany, NY

Rally and March for Aref and Hossain, 2009

Cornel West famously said, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” I think he refers to the Greek term for one of the categories of love, agape, love for humankind. Inspired by his metaphor, I think justice is a unique promise made by the government to each individual, guaranteed by the Constitution: equality under the law. We all know justice when we see it, whether prefaced by an adjective to specify our own unique interest—economic, legal, climate, cultural, racial, social—and we all know when we don’t see it. Justice doesn’t reside in one place—not in a founding document, judge, courtroom, courthouse, street, the police––though those are the town criers that distribute it (or not). It’s the capacity for love located in all of us, in our humanity, working together to keep the promise because it is to our individual and collective benefit to do that.

So what happens when the promise is broken?

There’s a reason the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which led to the formation of a new government based on racial justice, wasn’t called the Reconciliation and Truth Commission. Truth is the first element of justice, and the harmed and harmer can’t reconcile until truth is present as the first step. In this photo, taken on Central Avenue in Albany, three children, one of them Muslim, look at a poster tacked to a storefront window that advertises a rally for two men. The poster’s image is reversed for the viewer, as was justice for the men; you have to be able to read backwards to decipher the message. “Muslim Solidarity Committee,” the main headline reads, “Rally and March In Support of Yassin Aref and Mohammed Hossain, Tuesday, August 4, 2009,” and the message is about the Aref-Hossain case from 2006, in which the FBI targeted two working-class Muslim men, one the imam of a Central Avenue mosque, the other a Central Avenue small businessman, and convinced a jury to convict them of material support for terrorism. “No terrorist activity took place,” said Deputy Attorney General James Comey at their arrests in 2004, but his words didn’t matter because the whole case was a “sting,” a fictional plot to entrap the men. In other words, everything that we all took for granted when it came to the legal promise of justice was unreal, invented, backwards: secret evidence, charges predicated on suspicion alone, mistranslations, prejudicial jury instructions, and an agent provocateur/informant who was paid handsomely by the FBI to bear false witness and elaborately lie, ruining lives and tearing the community apart in the process. There was no truth presented; there were no terrorists; there was only the broken promise of justice and fifteen years in federal prison for each man, and that was good enough for a citizenry that was still in fear from 9/11 and saw every Muslim as a potential jihadist. Over the course of those fifteen years there were hundreds of other such cases nationwide: Muslims targeted, the battering ram of the law born down on them, their families, their mosques, their communities.

“Justice will not be served until those who are unaffected are as outraged as those who are,” said Benjamin Franklin, and by this photograph, I—who until this case counted myself as one of the unaffected—tried to capture the fear that the preemptive prosecutions of Muslims caused not only in Albany but throughout the U.S. The Muslim girl points to the picture of Mohammed Hossain, one of the convicted men, and the alert, at least, is on her, because she wears a hijab, though it’s no coincidence that all the children, the poster-readers, are Black––no strangers to such racism: different reason, same outcome. I took the photo from inside what was then the Central Avenue pizzeria owned by Mohammed Hossain, and I saw her pointing at both the absent owner and a way out, because the poster was put up by a group of citizens who said this is not justice, instead it was the law read backwards, just as the poster text appears reversed. I was a member of that group, and we organized this and other marches, rallies, and events for fifteen years until the men were free so no one would forget them and their families, and so an injustice like this would not happen again, at least not in Albany. Over the years we tried to get the truth out and keep the promise of justice, or at least reinstate it, and all these years later I think we did.

Photo: “Dissent in Albany Collection,” Albany Institute of History and Art

*Picturing Justice is a trademark of the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, used with permission